News & Opinions of Peter Tremayne VSHP - 2019

Feel free to comment at my Email Contact: harvardflyer@charter.net

Brothers in Arms - 41 Squadron |

|

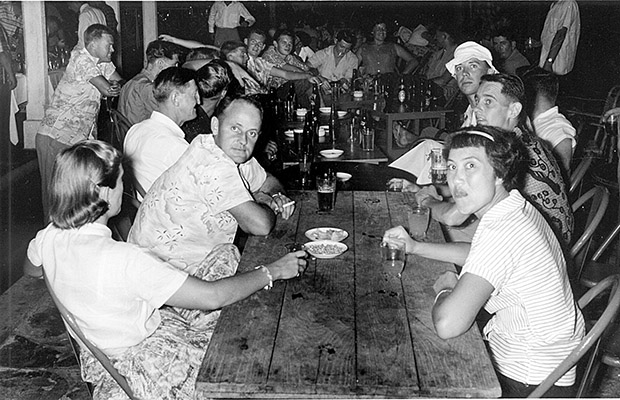

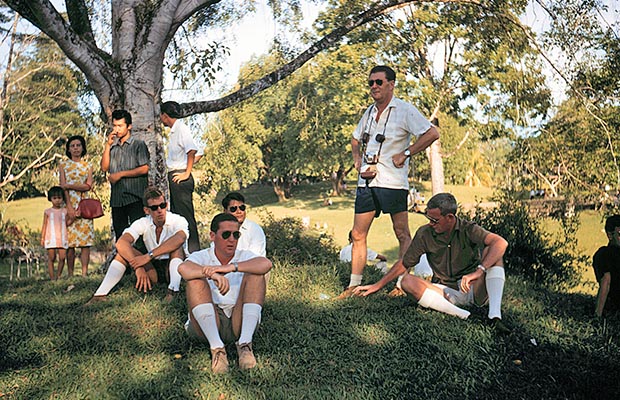

"These mist covered mountains are home now for me In early April of 2019, I traveled to Christchurch to attend a Reunion of the surviving members of No.41 Squadron of the New Zealand Airforce; a military unit based in Singapore from 1955 to 1977. This Squadron, operating Bristol Freighter aircraft throughout Southeast Asia, was involved in two British wars (Malayan Emergency & Indonesian Confrontation) and one American (South Vietnam). I served for various periods as a pilot with the Squadron from 1960 to 1975, on the final occasion during the last days in Saigon. The Reunion was held at the Royal New Zealand Airforce Museum at the now closed airbase of Wigram, the Base where I learned to fly in 1957. Some profound nostalgia; meeting with contemporaries from those long ago days and being close to the actual aircraft I'd flown back then -- old metal friends preserved for viewing only: No more to slip the surly bonds of earth and dance the skies on laughter-silvered wings in the long delirious burning blue. (thanks Pilot Officer McGee RAF 1940). For me, the most notable event of the Reunion was basking in the early Autumn sun over the Canterbury Plains, drinking excellent Speights beer with old friends: Terry Knight, Hugh Francis, Graeme Stagg, Alan Chung and Gary Danvers. May the Force be with you guys -- always! Peter Tremayne, May 28, 2019

|

|

No.41 Squadron RNZAF - A Revisionist History in 2019? |

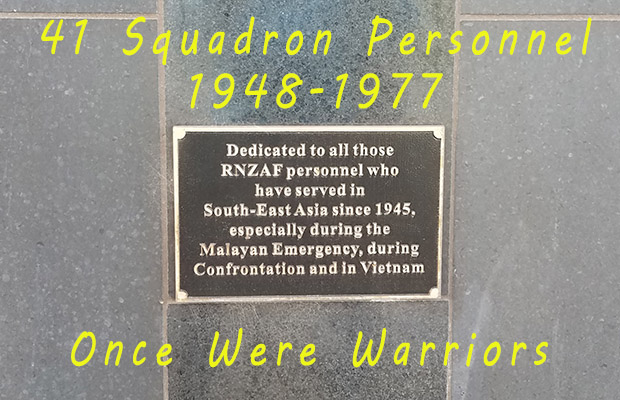

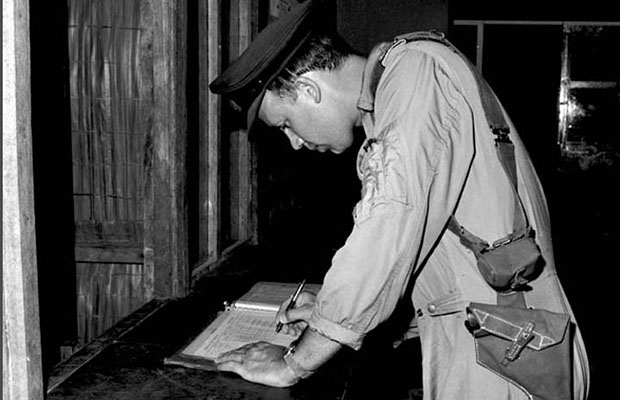

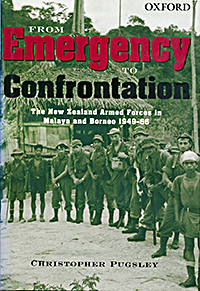

This statement is erroneous, either by ignorance or perhaps deliberately; hiding the truth about the many "Warlike" operations the Squadron was involved in from 1948 (Malayan Emergency) to 1975 (Last Days in Vietnam). The reality is that No. 41 Squadron was involved in shooting-war operations for much of its time in SE Asia. I'd appreciate any feedback as to when and where the Vampires, Venoms, Canberra's and Skyhawk's of 14 and 75 Squadrons, were ever in danger of being shot at during operations from 1955 to 1975? Scotty Winfield, and the NZDEF Personnel Archives and Medals Department recently discovered there were huge gaps in the paper trail concerning No. 41 Squadron’s activities in the 1960’s through to the early 1970’s. It appears that rectifying the omission of the GSM 1992 (Warlike) Vietnam clasp medal being issued to our ground-crew members has been well handled by Scotty, and from information contained in our aircrew logbooks. However, my long term complaint about lack of, or omission of awards during the same period, has been reawakened by this new information concerning lost records. If those lost records include Flight Authorization Books, the documents that show details and approval of each flight, including the aircrew members and assigned mission, I really do have a beef with the RNZAF senior leadership of that time, from our Squadron Commanders, all the way up the chain to the Chiefs of Air Staff. First, let me set the scene for Borneo Operations: In August 1965, I flew to RAF Kuching, Sarawak to begin Air Supply operations to the jungle forts An emerging factor in operating the Freighter in this hostile environment was the lack of a second pilot. From their introduction, the RNZAF Freighters were configured for one pilot only, except for two aircraft equipped with dual controls, used for conversion training and routine check-rides. For the Sarawak operations it was quickly determined that during the actual drop sequences close to the border, two pilots would occupy the front seats that would be equipped with dual controls. Since the Squadron was unlikely to have one of the two dual equipped aircraft in its fleet of four aircraft, it was necessary to jury-rig a number of single pilot aircraft with dual controls that would be exclusively assigned for airdrop operations in Borneo. My purpose in highlighting what this conflict between the Indonesians and ourselves was like, is to remind those who were not there, too young to remember, or not taught the history of a conflict that became known as the “Undeclared War”. Undeclared it may have been, but it was an authentic and dangerous war for soldiers on the ground and airmen in the sky. If it wasn’t a serious conflict, why did we carry Sterling submachine guns, why did we require a second pilot in the cockpit during airdrop operations, why did we need fighter aircraft cover, why did we require a daily Intelligence brief as to the disposition of the enemy and why were our drop loads often made up of many howitzer shells that the forts could fire into Indonesian territory to protect us from ground to air gunfire? If the Squadron records relating to these operational missions have been lost and/or the Unit History was written with omissions, then perhaps it’s all been forgotten (and never happened) in official NZ DEF records? Fortunately there are books like Christopher Pugsley’s and better still, most of the aircrew, like me, retain detailed Flying Logbooks of the events. My Logbook from that time shows that by early September 1966, I had completed a total of 162 “Operational” airdrop missions and delivered a total of 1,049,039 pounds of supplies. I can’t speak for the other aircrew members involved, but would make a guess that many of the pilots, navigators’ and signalers would have exceeded 100 missions.

Secondarily, let me set the scene for No. 41 Squadron's many years of involvement in South Vietnam, from my first experience in 1960 to the final days in April of 1975: From March to December 1960, my logbook shows eight flights in and out of South Vietnam, mostly on route to or from Hong Kong, landing at either Saigon or Tourane (later called Danang) for fuel. Then, from 1965 until 1968, I operated in and out of South Vietnam with 41 Squadron on forty flights; some on transit between Singapore and Hong Kong, but most on in-country flights from Saigon to Qui Nhon, Nha Trang or Vung Tau. During this time the sky above South Vietnam was a dangerous place if you couldn't locate your position accurately (with TACAN), or squawk a transponder code for friendly radar to see you (using IFF), or communicate with the right people (using UHF); all military avionics equipment not available in our Bristol Freighters during those years. A reality of the South Vietnam aviation world was the presence of many WW2 sky-trash airplanes, operated by the US military, the CIA's Air America and others. These airplanes: C-47's, C-46's, C-123's, Caribous etc, were close cousins of the Bristol Freighter, but had been upgraded with the latest avionics - capable of surviving in this American war zone environment - turning pig's ears into silk purses! The irony for us at 41 Squadron in our Bristol Freighters, was by mid 1966, the RNZAF had experienced its most significant and best fleet upgrades since WW2: C-130H's, P3B's and UH1D helicopters - all equipped with the very latest American military avionics. So what about us at 41 Squadron, risking our necks on a regular basis over Vietnam with Marconi radio equipment from the Titanic? This was a bizarre wartime omission pulled straight from the pages of Joseph Heller's Catch-22. "if you got by without this equipment, then you obviously don't need it"? My last foray into the war zone of South Vietnam was as a safety pilot on 41 Squadron's Bristol Freighters in April 1975. This assignment took place during the final days of freedom from Communist rule for the South Vietnamese people, and the fall of Saigon. I consider this 41 Squadron operation to be some of the most dangerous days in post-WW2 history of any RNZAF Unit, and yet, RNZAF and NZDEF senior officers have to this day ignored the fortitude and courage of the personnel involved under the leadership of Squadron Leader Bob Davidson. See my "Last Days in Vietnam" story below.

©Peter Tremayne, May 28, 2019

|

The Last Days in Vietnam - 41 Squadron Was There |

During the 41 Sqn Reunion at Tauranga in March 2017, Denis Monti and I were reliving our best and most dangerous moments during the last days in Vietnam. Our best, was conspiring to relieve the South Vietnam Air Force of at least one of their C-130’s, before the aircraft were captured by the North Vietnamese attack force. We’d made overtures to the Lockheed Rep in order to understand the fuel loads, security measures and door locks. Our daring-do plan was to get one started in the quiet hours of the night (no such thing with low level tracer crossing the airfield), and leap into the sky then head for Singapore. Dennis and I were both experienced C-130 H pilots, but our dilemma was having no idea how to start a C-130 A, without the Flight Manual, and in the dark? So in the event, this exciting air-pirating act never happened by us. Ten years later, I’m flying B-727’s for Orion Air out of North Carolina and we have First Officer Kim Pham – 'from Vietnam' who did hijack a C-130 A from Saigon, flew to some Delta airstrip, picked up his family and friends and flew to Singapore. He told me that he had total passengers on-board of around 300, with 30 in the cockpit. They’re small people, but think about that … the mind boggles! The worse experience was flying to Vung Tau from Saigon, an airfield we knew well from Freighter and C-130 flights from Singapore during the actual Vietnam war. Most of our refugee supply missions had been to An Toi Island, and the Vung Tau mission was considered a little dodgy from the outset (bad Intel). On April 8th, I flew (as Safety Pilot) to Vung Tau with Don Carter and crew and this was the scariest of those final trips. Nobody on the ground to be seen, and after shutting down the engines all we heard was continuous gunfire, so with great haste we climbed back aboard, started the engines and took off still carrying the cargo of rice. During the takeoff, with constant gunfire coming from our left side, I’m not ashamed to admit I crouched down on the step behind Don Carter, fully expecting the left window to shatter with incoming rounds, and had planned how to reach the control wheel if Don was hit, then firewall the throttles, and get his body out of the pilot seat. I retain a photo of the doomed USAF C5 Galaxy taxing for takeoff at Saigon, loaded with orphans and nurses. One hour later it returned (with great difficulty – no rudder or elevator controls – rear door blew off at approx. 30,000’). The crew got it back to within 1-2 miles of the runway at Saigon, then lost pitch control and skidded along on the paddy fields. All bloody sad; we were there on the ramp as the choppers flew in the dead and dying. At my UPS airline during the 1990’s, I operated with a retired C5 Galaxy pilot, who knew that Saigon accident crew. He explained how they’d managed to control the airplane by differential power, and probably would have reached the runway if they’d not dropped the gear at the last moment, an action that messed with the “damped pitch oscillation” they’d achieved.

©Peter Tremayne, May 28, 2019 |

The Missing Years of 41 Squadron in "Portrait of an Air Force" |

A few days ago I received a comment from Glen McCullough kindly pointing out my omission of 41 Squadron's considerable participation in SEATO's Chapter 21 provides very detailed information on the RNZAF Squadrons' 14, 75 and 41 during the Malayan Emergency from 1955 through to 1960, in particular, the ground attack missions (Firedogs and Smash Hits ... killing rubber trees and the occasional unlucky Orangutan) by 14 Squadron Venoms. These attacks were worthy of DFC awards for the brave pilots! After 1960, the authors have included a host of details (including fascinating, but useless minutiae) of 75 and 14 Squadron’s activities with their Canberra bombers, that ultimately led to the commitment of 14 Squadron at RAF Tengah in 1964, for the beginning of Indonesian Confrontation, until its withdrawal in October 1966. At this point in the book, there’s a delightful (for the real Dogs of War) comment: “When 14 Squadron returned to Ohakea in November 1966, The New Zealanders had neither dropped a bomb nor fired a rocket in anger during the Confrontation.” As for 41 Squadron’s activities after 1960, Chapter 21 covers the two significant Detachments from RAF Changi to Korat in northern Thailand, the first in May 1962 for Operation Scorpion and the second in January 1963 for the program known as SLAT. This detachment remained in Thailand for two years, finally returning to Changi in February 1965. The authors have provided mission statistics for the SLAT operation: Two aircraft flew 647 courier flights, carrying 3,500,000 lbs of freight, 92,000 lbs of mail and 15,877 passengers. Precise details obviously garnered from comprehensive archival sources in New Zealand. When we come to the section in Chapter 21 that addresses the Squadron activity for the period mid-1965 to late 1966, I was not surprised to find little written, with the exception that Ian Hutchins took over the Squadron from Roger Garrett, and a brief account of Noel Rodger and crew taking hits from ground fire near the Indonesian border in Freighter NZ 5906. As members of a “Ghost Squadron” that participated in a shooting war for more than a year in Sarawak, we have a mystery as to why the 41 Squadron airdrop operations from RAF Kuching are not available in any detail. There’s nothing written about mission statistics, being shot at when close to the border, lousy afternoon weather, poor visibility, tricky navigation, and often a seven day week on operations? Let’s study statistics as I see them: I personally flew 162 operational airdrop missions and dropped a total of 1,050,000 lbs during the twelve months from August 1965 to September 1966. During that same period, it would be reasonable to suggest that another 1000 missions were flown by other crews, dropping a total of 6,500,000 lbs. Impressive figures when you realize the drops were supporting combat troops at the jungle forts. Very much Active Service duty.

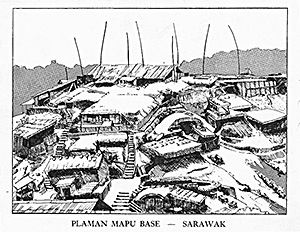

My second shooting story is about an airdrop at Plaman Mapu sometime in the first six months of our Kuching operations. Our drop load included many shells for the Fort’s Pack Howitzer, and after a few circuits over the DZ, their radio man requests a priority to drop the boxed shells before the remainder of the load. When asked the reason, he stated that “the enemy” were shooting at us on every circuit, including 20 mm Canon, and the Fort is trying to neutralize the threat by pounding them with their Howitzer. This was a learning moment for us, that often close to the Border, the British, Aussie and Kiwi Army guys would not tell us that we were being fired on, just in case we might run away without finishing the drop! My third shooting story is tragic: I’m having a typical tasteless (except for the vinegar in the poached eggs) British Army breakfast at RAF Kuching, trying to get my head together for Major Bloodnock’s (Major Cocksedge in real life) Intel briefing at 0800 hours. “The location of the enemy is here, here an here” “That’s nice, can we go fly now?” Anyway, across the breakfast table from me is an RAF Flight Lieutenant pilot, about my age, who’s going on his first Borneo mission, in a Whirlwind helicopter from RAF Kuching to the jungle fort at Stass – Red 21, and asks me whether it’s challenging to find. So I pull out my scruffy Topo map and give him the bearing from Kuching airport to Stass of 256° Mag and a distance of 23 nm. Takes the Freighter 10 minutes from take off, so maybe 15 minutes for you? We leave the Officers Mess in our flight suits and brown suede brothel-creeper boots stumbling down to the Armory to be issued with Stirling sub-machine guns (with two mags of 30 x 9 mm rounds), and across the Pieced Steel Planking (PSP) to the briefing room. Greeted to the usual bumff from Major Bloodnock (where the enemy is) local weather for the day (no morning clouds, bad visibility from burning hill rice in Irian Jaya, and afternoon thunderstorms), and assigned the airdrop missions for 41’s Bristol Freighter and 215’s RAF Argosy – the “Whistling Wheelbarrow”. I parted ways with the newbie Borneo Whirlwind pilot, wishing him a good flight to Stass … never to see him again. That afternoon, there’s a report from Stass that a Whirlwind was shot down by enemy gunfire close to the Border and the pilot was last seen running through the jungle firing his machine-gun at Indonesian military pursuers. It's now 2019, and the surviving aircrew members that took part in the Kuching Detachment Airdrop operations are getting thin on the ground, so it’s critically important for us to provide NZDEF and the Air Force Museum with the missing information on what 41 Squadron Bristol Freighters really did in Sarawak during Confrontation, from August 1965 to September 1966. For us that remain, still remembering all the great, and often courageous, things we did over the jungles of Sarawak, don’t let those memories be lost, like tears in the rain (thanks Bladerunner).

©Peter Tremayne, October 8, 2019 |

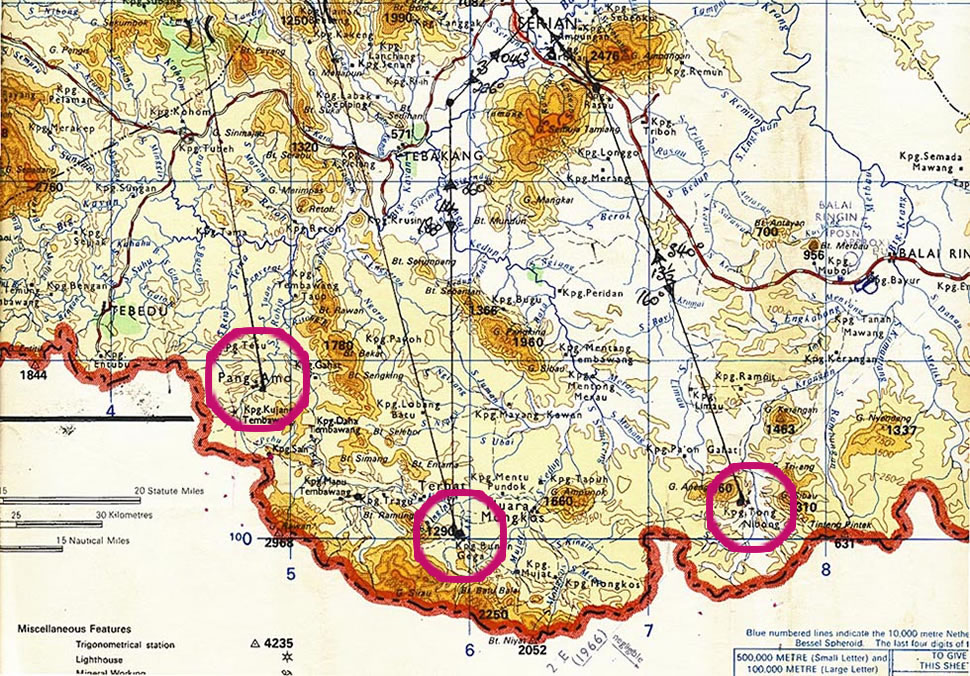

Down on the Border: On the left is Pang Amo,then Plaman Mapu and Nibong on the right.The grid squares are approx 5 nm, so note the distance of each fort from the Border |

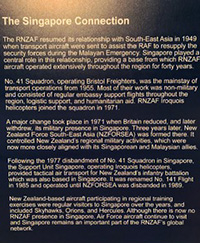

During my visit to the RNZAF Airforce Museum at Wigram for the No. 41 Squadron Reunion, Graeme Stagg brought to my attention a display board entitled "The Singapore Connection" (photo on the left). The second paragraph reads as follows: No. 41 Squadron, operating Bristol Freighters was the mainstay of transport operations from 1955. Most of their work was non-military and consisted of regular embassy support flights throughout the region, logistic support, and humanitarian aid.

During my visit to the RNZAF Airforce Museum at Wigram for the No. 41 Squadron Reunion, Graeme Stagg brought to my attention a display board entitled "The Singapore Connection" (photo on the left). The second paragraph reads as follows: No. 41 Squadron, operating Bristol Freighters was the mainstay of transport operations from 1955. Most of their work was non-military and consisted of regular embassy support flights throughout the region, logistic support, and humanitarian aid.  along the Kalimantan border with Indonesia. The British, Australians, Kiwis and some Malaysians were in a shooting war against regular Indonesian military units along that border, including a fighter threat from MIG-21’s based at Kalimantan airfields. The RAF’s No. 20 Squadron [Fighter] was on hot alert with Hunter aircraft at the end of the Kuching runway to provide air cover if our Bristol Freighter or the RAF’s Argosy were attacked by Indonesian fighters while we were circling the jungle forts, on station, very close to the border and Indonesian guns, for over an hour. This initial commitment of New Zealand combat forces and air support is highlighted on page 224 of Christopher Pugsley’s “From Emergency to Confrontation” and my name is there! At that time I was the Squadron Training Officer, and as such, designated to train the other pilots on this latest operational task.

along the Kalimantan border with Indonesia. The British, Australians, Kiwis and some Malaysians were in a shooting war against regular Indonesian military units along that border, including a fighter threat from MIG-21’s based at Kalimantan airfields. The RAF’s No. 20 Squadron [Fighter] was on hot alert with Hunter aircraft at the end of the Kuching runway to provide air cover if our Bristol Freighter or the RAF’s Argosy were attacked by Indonesian fighters while we were circling the jungle forts, on station, very close to the border and Indonesian guns, for over an hour. This initial commitment of New Zealand combat forces and air support is highlighted on page 224 of Christopher Pugsley’s “From Emergency to Confrontation” and my name is there! At that time I was the Squadron Training Officer, and as such, designated to train the other pilots on this latest operational task.  Although we, from the British Commonwealth military, joke that Americans get their medals out of cornflake boxes, I do like the objective system they use for gallantry awards: A DFC is awarded after completing 100 operational missions or sorties, whereas, in the RNZAF of my time, you couldn’t expect a commendation for an AFC or DFC if your senior officers didn’t like you, or they hadn’t got theirs. I suspect the reason many of our Huey pilots assigned to the RAAF unit in Vietnam were awarded DFC’s (for very valid reasons), was the objectiveness of the Aussie commanders. Also, Fg Off Mike Callanan flying in Vietnam as a FAC with the USAF was awarded an American DFC after 100 missions. So what happened to our very active participation in the Undeclared War? To my knowledge, the only award for 41 Squadron’s part in Confrontation was a MID for Flt Lt Noel Rodger. No DFC/DFM's, no AFC/AFM's … as there had been during the Squadron’s participation in the Malayan Emergency, doing precisely the same type of airdrop operations, but in a non-hostile "being shot at" environment.

Although we, from the British Commonwealth military, joke that Americans get their medals out of cornflake boxes, I do like the objective system they use for gallantry awards: A DFC is awarded after completing 100 operational missions or sorties, whereas, in the RNZAF of my time, you couldn’t expect a commendation for an AFC or DFC if your senior officers didn’t like you, or they hadn’t got theirs. I suspect the reason many of our Huey pilots assigned to the RAAF unit in Vietnam were awarded DFC’s (for very valid reasons), was the objectiveness of the Aussie commanders. Also, Fg Off Mike Callanan flying in Vietnam as a FAC with the USAF was awarded an American DFC after 100 missions. So what happened to our very active participation in the Undeclared War? To my knowledge, the only award for 41 Squadron’s part in Confrontation was a MID for Flt Lt Noel Rodger. No DFC/DFM's, no AFC/AFM's … as there had been during the Squadron’s participation in the Malayan Emergency, doing precisely the same type of airdrop operations, but in a non-hostile "being shot at" environment.  Now in 2019, living as an American Citizen, bombarded for the last two years by the corrupt US Media, Democrat Party and Neo-Communists, that my vote for Trump doesn’t count, I’m reminded of those treacherous actions in April 1975 by the Democrat Party held Congress. There’s that dramatic moment when New York Senator Jacob Javits tells President Ford, “I will give you large sums for evacuation, but not one nickel for military aid.” The 2014 PBS documentary Last Days in Vietnam highlights the problem Republican President Ford faced in providing fresh military aid for the SVN Forces, and why every American soldier who fought, or died (56,000?) was ultimately betrayed by their Government and Country. I also learned from the movie that the Peace Accord stated that if the NVN did move into SVN again, the US would come back with full force (massive air-strikes?), and Ho Chi Minh was terrified that President Nixon would do just that. Unfortunately, Nixon was maneuvered out of power (by the Left Wing Media and Democrats), so it then became "Open Season" for the North Vietnamese to move south again.

Now in 2019, living as an American Citizen, bombarded for the last two years by the corrupt US Media, Democrat Party and Neo-Communists, that my vote for Trump doesn’t count, I’m reminded of those treacherous actions in April 1975 by the Democrat Party held Congress. There’s that dramatic moment when New York Senator Jacob Javits tells President Ford, “I will give you large sums for evacuation, but not one nickel for military aid.” The 2014 PBS documentary Last Days in Vietnam highlights the problem Republican President Ford faced in providing fresh military aid for the SVN Forces, and why every American soldier who fought, or died (56,000?) was ultimately betrayed by their Government and Country. I also learned from the movie that the Peace Accord stated that if the NVN did move into SVN again, the US would come back with full force (massive air-strikes?), and Ho Chi Minh was terrified that President Nixon would do just that. Unfortunately, Nixon was maneuvered out of power (by the Left Wing Media and Democrats), so it then became "Open Season" for the North Vietnamese to move south again.  Operation Scorpion based at Korat, Thailand from May 1962. My mistake was due to a lack of personal involvement with the Squadron’s activities between early 1961 and mid-1965. To help me understand this period I dusted off my aging copy of Portrait of an Air Force, published in 1987 by Geoffrey Bentley and Maurice Conly ©RNZAF Museum Trust Board. In this well-researched book, Chapter 21-The Malayan Emergency and Confrontation with Indonesia covers the period that 41 Squadron was most active in "Warlike" operations between 1955 and 1966. Later in the book, the Squadron’s participation in the South Vietnam War from 1965 to 1975, is well detailed in Chapter 23 –Service in Vietnam.

Operation Scorpion based at Korat, Thailand from May 1962. My mistake was due to a lack of personal involvement with the Squadron’s activities between early 1961 and mid-1965. To help me understand this period I dusted off my aging copy of Portrait of an Air Force, published in 1987 by Geoffrey Bentley and Maurice Conly ©RNZAF Museum Trust Board. In this well-researched book, Chapter 21-The Malayan Emergency and Confrontation with Indonesia covers the period that 41 Squadron was most active in "Warlike" operations between 1955 and 1966. Later in the book, the Squadron’s participation in the South Vietnam War from 1965 to 1975, is well detailed in Chapter 23 –Service in Vietnam. Being shot at from the Indonesian side of the Kalimantan Border was a constant threat when circling to drop at the forts, particularly those DZ’s very close to the borderline such as: Pang Amo (Red 33), Plaman Mapu (Red 336), Nibong (Red 352) and Stass (red 21). I don’t recall which DZ Noel Rodger and crew were servicing, but it was either Pang Amo or Plaman Mapu, but whichever, a small error in circling at those DZ’s (over featureless jungle) was enough to be in the range of hostile gunfire. In the event, they simply had a bad day, and a lucky escape. Three significant side notes: In June 1967, I was with a Bristol Freighter crew flying from RAF Changi to Perth via Bali, Port Hedland, and Carnarvon. At Bali, we spent the night at the Hilton Hotel, and there, a young Indonesian waiter comments on our RNZAF uniforms with the New Zealand patch on the shoulders. He spoke excellent English, and we told him we were flying a Bristol Freighter from RAF Changi to Australia, and he explained his recent background as an Indonesian Army officer serving on the Kalimantan Border with Sarawak in 1965-66. He then surprised us by revealing he was on the Border when his Unit shot down a New Zealand Bristol Freighter. I told him the Freighter flew away to fight another day, but he wouldn’t believe me, even when I explained that I’d flown that airplane back to Singapore the night after the incident … and it whistled all the way across the South China Sea because of the bullet holes!

Being shot at from the Indonesian side of the Kalimantan Border was a constant threat when circling to drop at the forts, particularly those DZ’s very close to the borderline such as: Pang Amo (Red 33), Plaman Mapu (Red 336), Nibong (Red 352) and Stass (red 21). I don’t recall which DZ Noel Rodger and crew were servicing, but it was either Pang Amo or Plaman Mapu, but whichever, a small error in circling at those DZ’s (over featureless jungle) was enough to be in the range of hostile gunfire. In the event, they simply had a bad day, and a lucky escape. Three significant side notes: In June 1967, I was with a Bristol Freighter crew flying from RAF Changi to Perth via Bali, Port Hedland, and Carnarvon. At Bali, we spent the night at the Hilton Hotel, and there, a young Indonesian waiter comments on our RNZAF uniforms with the New Zealand patch on the shoulders. He spoke excellent English, and we told him we were flying a Bristol Freighter from RAF Changi to Australia, and he explained his recent background as an Indonesian Army officer serving on the Kalimantan Border with Sarawak in 1965-66. He then surprised us by revealing he was on the Border when his Unit shot down a New Zealand Bristol Freighter. I told him the Freighter flew away to fight another day, but he wouldn’t believe me, even when I explained that I’d flown that airplane back to Singapore the night after the incident … and it whistled all the way across the South China Sea because of the bullet holes!